SOVEREIGNTY, NOBILITY AND ROYALTY

Non-reigning Sovereigns and Royal Families

(Note: The following article is built on a traditional sense of Western European justice, history and philosophy as well as the law of nations which affirms that under certain circumstances, that are well-defined, former ruling families possess permanent, unending and inalienable rights—the right to legal and rightful sovereignty and the right to honor and be honored as such. These are the same rights accorded to any authentic governments-in-exile.

However, these special rights can be permanently lost. And if lost, they die forever or become extinct and cannot be retrived, rehabilitated or reconstituted unless a higher secular sovereign with appropriate jurisdiction rights over the territory in question exists and restores it. Otherwise, there is no possibility for any kind of restoration.

All the major legal principles that promote genuine and authentic nobility, royalty and chivalry are contained in the following new two volume book. Note what is says in the first paragraph of the Foreword:

The whole field of nobility and royalty is in disarray and confusion. It is rife with falsehoods, misguided experts, phony princes, and counterfeit chivalric orders. Besides the numerous scams and charlatans that exist, there is a widespread misunderstanding of the international and natural laws that govern dynastic rights. This is a field that is truly divided. This sad state of affairs need not continue. If international law is honored, revered and respected, then everything can be set in its proper order. The grand key to this needed unity is the rule of the just, time-honored laws that already exist.

The author is Dr. Stephen Baca y Kerr, JD, LLM, MAT, former special counsel to the Imperial and Royal House of Habsburg, Professor and Dean of the Law School at the International College of Interdisciplinary Studies. His book is The Entitlement to Rule: Legal, Non-Territorial Sovereignty in International Law and it is a masterpiece. Note excerpts of what people have said about it:

“It is written in a clear and compelling manner. It is hoped that more and more people will become familiar with the laws of justice contained in this book.” (Thubten Samphel, director of the Tibet Policy Institute of the Central Tibetan Administration and author of the book Falling Through the Roof, Dharamshala, India)

“It is magnificently done and of great worth.” (Adalberto J. Urbina Briceno, Sc.D., Professor Head of the Public International Law Chair of the Catholic University Andres Bello- Caracas)

“It is a goldmine of references and is a valuable account of a [thought provoking] . . . and poorly understood area of law.” (Rev’d Professor Noel Cox, LLM, MA, MTheol, Ph.D., LTh, FRHists, Barrister, Aberystwyth University, New Zealand)

“Dr. Kerr has put together a book that is a “one of a kind” providing what is needed to perpetuate the rights of deposed sovereignty. For all those interested in the legal future of nobility and royalty, this is a very important, scholarly and insightful book to read.” (LaWanna Blount, Ph.D., F.Coll.T, vice president and professor at the American College of Interdisciplinary Sciences, Como, Mississippi, USA)

“Dr. Kerr’s book . . . is one of those . . . path breaking works that throws new light on a field of study . . . on the complex legal and philosophical sinews that keep alive [deposed] monarchies. . . . This type of writing fills a huge gap within the royal studies field. . . .” (Dr. Diana Mandache, historian and author, Budapest, Romania)

“The author obviously has a deep understanding of international law and how it relates to deposed monarchies and exiled governments. The content is well structured and well written. I accept this book as conforming to the highest academic standards expected of a master scholar and practitioner.” (Alexander Arapov, Sc.D., Professor of the Department of Philosophy and Sociology of the All-Russian State Distance-Learning Institute of Finance and Economics, a branch of the Financial University of the Russian Federation)

“This has been the most interesting and helpful book I have read in the field of nobiliary law as well as international law . . . . It exemplifies the highest level of scholarly content, clarity and depth of inquiry yet presented on this profound and important subject.” (Prof. Dr. Mirjana Radovic-Markovic, Academician, Institute of Economic Sciences and Faculty of Business Economics and Entrepreneurship, Belgrade, Serbia)

This unique book is being offered for free because of its singular importance to the field of nobility and royalty. Go to the website: www.the-entitlement-to-rule.com.

For additional important insights on sovereignty see:

“DEPOSED SOVEREIGNTY AND ROYALTY: how to preserve it and how it can be lost”

Subheadings

Click on whatever is of interest to you:

Introduction to Sovereignty:

Sovereignty / Secession, Rebellion, Referendums and Sovereignty / Sovereignty as Protective / International Law

Royal Rights and Sovereignty:

Rights / Sovereignty and Ownership / The Legal & Moral Right to be Restored / Sovereignty is Permanent and Forever, but It can be Lost on both a “Defacto” and “Dejure” Basis / Abdications, Renunciations and Annexations / Tiny Sovereign Nations / Sovereignty and Mediatization / Permanent Rights unless Forfeited / Exiled Sovereignty: Tibet / Exiled Sovereignty: The Maharajahs and Princes of India / Sovereignty: Ethiopia and other Great Examples / The Myth of Popular Sovereignty and the Rule of Law / The King and the Constitution as well as How Sovereignty can be Premanently Lost / Ownership and Property Rights / Royal Adoptions / Sovereignty and Royalty / Sovereign Equality / The Buying and Selling of Sovereignty

Conclusions:

Legal Realities / The Future of Nobility and Royalty / References

Introduction to Sovereignty

Sovereignty

From the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth, there seems to have been some change in focus and discussion, but despite these philosophical movements, “The principle of sovereignty, whatever its precise scope, still thrives in international law and international relations.” (www.law.ufl.edu/faculty/publications/pdf/sov.pdf) In fact, “. . . sovereignty remains a central organizing principle of the international system.” (Katherine L. Lynch, “The forces of economic globalization: challenges to the regime of International Commercial Arbitration,” 2006, p. 62) This critically important concept is fundamental to justice and therefore to the future of nobility and royalty. For example, “de jure” sovereignty in an ex-monarch, and his lawful successors, is legally defendable as they represent perpetual rights and privileges that are just, permanent and inalienable.

In fact, “These rights [the royal prerogatives of granting noble titles, honors and knighthoods] are ingrained in [inseparably connected to] the concept of sovereignty. . . . In fact, they form an authentic ‘privilege,’ which cannot have any theoretical justification [or legitimacy] outside of ‘sovereignty’. . . .” (www.consiglioaraldico.com

/eng/3/index.php) In other words, sovereignty lies at the very heart of all royal prerogatives. Without either “de jure” or regnant sovereignty, there are no royal rights.

Two words, “de jure” and “defacto,” need to be understood before we proceed as they are significant in terms of possessing royal prerogatives, which, again, is at the core of legitimacy. The best way to describe them is in the context of government. Herbert W. Briggs, a well published legal scholar, wrote:

A de jure government is one which . . . ought to possess the powers of sovereignty, though at the time, it many be deprived of them. A de facto government is one which is really is possession of them, although the possession may be wrongful or precarious. (“De Facto and De Jure Recognition,” The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 33, No. 4 (October 1939), p. 689)

“De jure” sovereignty is rightful sovereignty dispossed of its territory and people, but still maintains its rights to lawfully govern. As an example, from 1962 to the present, based upon current international laws and conventions, the “International Commission on Orders of Chivalry” concluded that, “. . . an exiled sovereign retains the right to bestow honours, dynastic, state or however styled. This right extends to their lawful successors.” (www.icocregister

.org/principles.htm) As a direct result, they have approved as valid over 40 some “de jure” titular Emperors, Kings, Princes and Dukes, heads of various royal families throughout the world, as rightfully presiding over 50 some dynastic orders of legitimate and authentic knighthood. In this, these men are exercising one of their most important privileges–the right to honor and reward merit by the authority of their ancient royal status. This Commission stated that even though these rights “. . . may not be officially recognized by the new government [that in itself] does not affect their traditional validity or their accepted status in international heraldic, chivalric and nobiliary circles.” (Ibid.)

Sovereignty is the foundation which justifies the existence of genuine nobility and royalty any where on earth. A claim to title, for example, is either authentic and true, or false, based on this fundamental bedrock principle. Without the concept of “de jure” or rightful non-reigning sovereignty, there is no foundation for the existence for any legitimate royals, nobles and lawful knighthoods that are not a part of a monarchy that is presently ruling a territory or country. Hence, this critical underpinning becomes the chief and abiding issue in determining the future of nobility and royalty. Without “de jure” sovereignty, there is no legitimate non-reigning royalty, and without authentic royalty rights, there is no nobility or genuine knighthood. The only founts of honor left on earth having any rightful royal prerogative (ius majestatis and ius honorum) would be the reigning monarchs. In other words, “de jure” nobility and royalty is inseparably connected to the law of sovereignty. It is also the key organizing principle that maintains nation-states. Therefore, there could hardly be anything more important to the future of mankind.

Sovereignty has been defined as:

. . . the supreme, absolute . . . power by which any independent state is governed [which encompasses] . . . the power to do everything in a state without accountability, — to make laws, to execute and to apply them, to impose and collect taxes and levy contributions, to make war or peace, to form treaties of alliance or of commerce with foreign nations, and the like. (Black’s Legal Dictionary: http://hawaii-nation.org/sovereignty.html)

These powers holds nations together and enable them to function, so in spite of some changes in international law, sovereignty itself is not becoming less relevant or important. It is, in fact, the mainstay–the chief or most prominent structuring principle in this world. The concept that sovereignty is inviolable, expressed in the United Nations Charter as “noninterference in the domestic jurisdiction of states” has been universally accepted and supported by all UN member nations. It has been called “the defining doctrine,” “the primary cause” from which flows all effective government, “the defining feature of statehood,” “the glue or cement that holds all society together,” “the one and only true stabilizing principle,” “bedrock,” “the foundation stone,” “the most

sacred of international law principles,” “an indispensible concept,” “of cardinal importance,” “the central organizing principle,” “the soul” of civilized society, “the reference point,” “the central concept for the preservation of world peace,” “the most basic principle in international affairs,” “the dominant world order framework,” doubtlessly “the most precious” of all governmental rights, “the cornerstone,” “the guiding principle,” “the key constitutional safeguard,” “the final and ultimate matrix of a stable society,” the “pinnacle,” the “ark of the covenant,” the “holy grail,” the “Alpha and Omega,” the “first principle,” “the “sine qua non of international law,” that is, the indispensable condition that cannot be done without, for it is “the building block,” “the principle of solidarity” — “safeguarding humanity.” Algerian President Boueteflika, while addressing the UN General Assembly in 1999, said, sovereignty is “our final defense against the rules of an unjust [and often unfair] world.” (www.idrc.ca/en/ev-28492-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html) Everything of real importance in government revolves around this chief governing principle.

Robert Lansing (1864-1928), a U. S. legal authority and author, declared that the “Sovereignty” is “. . . the fundamental authority which controls, restrains and protects man as a member of society.” (Notes on Sovereignty in a State, 1 AJIL, p. 105 (1907) Jeremy A. Rabkin, a professor of government at Cornell for 27 years, concurred that sovereignty, “. . . is central to the maintenance of effective, constitutionally constrained political systems . . . [and that it has the important power to] protect individual liberty,” something of immense worth to be treasured and vouchsafed. (Law Without Nations? Why Constitutional Government Requires Sovereign States, 2005) (Review: www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?issueID

=50&articleID=649) Kalevi Jaakko Holsti wrote in his book, Taming the sovereigns: institutional change in international politics:

Those who have sought to create international systems on bases other that the sovereign state — such as Napoleon, Stalin and Hitler — have had their enterprises de-legitimized. . . . None of these empire-builders generated much international support precisely because they wanted to destroy the Westphalian states system and replace it with structures that denied the principle of sovereignty. (University of Cambridge, 2004, p. 118)

Sovereignty is the critical principle needed to safeguard the nations and protect our basic and most important fundamental rights from usurpation and encroachment of other states or global powers. It is well entrenched in legal and political discourse. Its philosophical and practical roots go back for hundreds, even thousands of years. It is part of the wisdom of the ages. This concept is a close cousin to the legal principle of the divine right of kings. In fact, sovereignty was created to protect the right of kings or the right to rule independent of outside forces. It is still used to protect nations from each other and promote decency and justice between nations. The whole idea of sovereignty is a fundamental anchor essential to the peace, well-being and cooperation of all nations.

Jeremy A. Rabkin, mentioned above, in his book, The Case for Sovereignty (AEI Press, 2004), describes a study that shows that a “post-sovereign” world would embolden and encourage terrorism, depress economic development and growth, erode national loyalties, promote lawlessness and crime, destabilize fragile countries and spur even greater international conflict and atrocities everywhere. (www.ashbrook.org/books/0844741833.html) In fact, members of the Overseas Development Institute in 2005 declared that for the future of mankind, “The [real] challenge is to harness the international system behind the goal of enhancing [promoting] the sovereignty of states – that is, to enhance [strengthen and build] the capacity of these states to perform the functions that define them as states.” (Working paper 253: www.odi.org.uk/publications/working-papers/253-sovereignty-gap-state-building.pdf) Strong independent sovereign states equals a strong, peaceful and law-abiding world.

Even globalists, who want a one world government to control all mankind, such as Richard Haass, President of the Council on Foreign Relations, recognized that there are “benefits [to state] sovereignty” and that “the basic idea of sovereignty . . . needs to be preserved.” (“Sovereignty and globalism,” February 17, 2006: www.cfr.org/publication/9903

/sovereignty_and_globalisation.html

The principle of sovereignty is a tremendous blessing, an important benefit, a supernal and precious asset, not a curse. No wonder, “several declarations and resolutions of the United Nations, as well as other important international covenants, recognize . . . that the sovereignty of every country is . . . absolutely indispensable . . . , and . . . condemn any violation of the sovereignty of countries as a . . . crime against humanity.” (www.anti-imperialist.org/sovereign-rights_1-18-04.htm) In fact, in some circles, sovereignty is considered to be the only true and authentic international law in existence. (See: “Soverignty in the Holy Roman and Byzantine Empires” & “DEPOSED SOVEREIGNTY AND ROYALTY: how to preserve it and how to lose it”)

Secession, Rebellion, Referendums and Sovereignty

Sovereignty is power, the highest kind of power known on earth, and it is inseparably connected to the land it rules over. The unmitigated right of an individual or group of people to secede with part of the territory of that nation does not exist. A person or group of people may move to another country and thus free themselves from some of their real or imaginary grievances, but they cannot rightfully take national territory that does not belong to them, that is, such cannot be done without the express approval of the supreme authority of that land. The point is, sovereignty is permanent and indivisible. Unless the ruling power, that holds the supreme right of sovereignty, willingly and freely, and without pressure, undue influence or duress, gives its territory away, no secession or division can rightfully take place.

This is necessary to protect the sanctity of a nation. In other words, if secession were a right, it would threaten the very fabric of society. It would institutionalize a powerful tool for special interest groups to bully the rest of the nation. For example, the rich who don’t like a certain policy could just secede, create their own nation and let the poor and underprivileged of their former nation wallow in ruin. Or, choke the rest of the nation into submission. Secession is the ability to destroy and dismember a nation, create instability, encourage malicious political manipulations and dishearten those who would otherwise invest in and build up the economy creating greater prospects and prosperity for all. Sovereignty, the supernal authority of a nation, is far above any so-called right to secede. U.N. Secretary-General U. Thant declared in 1970:

As far as the question of secession of a particular section of a State is concerned, the United Nations attitude is unequivocable. As an international organization, the United Nations has never accepted and does not accept and I do not believe it will ever accept the principle of secession of a part of its Member States. (Secretary-General’s Press Conferences, in 7 U.N. MONTHLY CHRONICLE 36 (Feb. 1970)

Self-determination is a noble sounding ideal, but in reality, it is a “golden calf” or “false god,” because one man’s “self-determination” is another man’s “pernicious and malignant rebellion against existing rights” — in other words, sedition and treason. Because self-determination has been worshipped and idolized, it is often exploited by would-be usurpers, rebels, and so-called freedom fighters who bring anguish, murder and pain, not greatness, prosperity and good to their countries. Self-determination is not greater than sovereignty. Sovereignty and territorial integrity remain supreme. Otherwise, there would be justification for infinite malicious mischief, national destruction and ruin. The Chinese people in San Francisco would rebel and create a new China in California and New York, the Kurdistan would create horror and start a blood bath in an effort to start up a new nation out of parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. We would have a nation of Blacks in Alabama, an Hispanic nation in the Southwest of the United States and the Swedes in Wisconsin along with every Indian tribe in the country that would secede and on and on it would go. We could have 8,000 to 10,000 little countries spring up all over. The Pakistanis in England would separate and forcefully create a new country and take part of the wealth and glory of London with them. And what would be left of any national government if everyone could just secede? It would destroy all nations and the prosperity, safety and security of all people. As far back as 1793 in the setting of the French Revolution, General Carnot reported to the National Assembly that:

If . . . any community whatever had the right to proclaim its will and separate from the main body under the influence of rebels, etc., every country, every town, every village, every farmstead might declare itself independent. (Lazare Carnot (1753-1823) war auch Mitglied der fanzösischen Nationalversammlung während der Revolution (zitiert nach: Emerson (1960) p. 299)

Nothing would be left if self-determination were to rule as the highest law of all nations. There must be limits to prevent national suicide and destruction. Common sense tell us that the right of territorial integrity must always take precedence over the right to self-determination. A good summary was given by a Commission of the League of Nations in 1921. On the importance of sovereignty, it concluded:

To concede to minorities either of language or religion, or to any fractions of a population, the right of withdrawing from the community to which they belong, because it is their wish or their good pleasure, would be to destroy order and stability within States and to inaugurate anarchy in international life; it would be to uphold a theory incompatible with the very idea of [sovereignty or] the State as a territorial and political entity. (The Report of the Committee of Rapporteurs, League of Nations, Doc. B/21/68/106 [VII] p. 22-23, April 26, 1921)

Hence, secession is an act of robbery in which an individual or group of people want to steal a portion of a nation’s land or territory. It is contrary to justice, what is fair and what is ethically or morally right. It is contrary to the principal of sovereignty, the supreme rights of a nation as a whole.

The use of referendums for anything of importance is also considered to be a grave mistake as it is a well-known researched fact that most people do not have the time or interest to spend hours identifying the deep, hidden issues or long-term ramifications of the proposals put before them. Most voters are not educated in State craft, in fact, they usually vote for very shallow reasons, like a good slogan or spin, good looks, a great command of speech, not the real issues, or because of clever manipulations, demagoguery or on account of the fact that a favored basketball or football player sponsers it. Referendums also tend to promote a kind of tyranny of the majority—a short-sighted, dangerous, mob mentality along biased racial, ethnic or religious grounds. Those who favor them tend to think all people are benevolent, rational, kind hearted and good natured, which is far from the whole truth. The general populace are not angels, pure, wise, thoughtful and knowledgeable. Many have extreme anti-social traits, such as venality, brutality, avariciousness, and murderous dispositions and would not shirk from destroying others and robbing them of everything of value, which is why we must have policemen to maintain some semblence of justice. Terrorists love referendums to make big changes through intimidating large groups of people and by ballot box tampering. Citizen initiated referendums are especially problematic as they prove, far too often, to be ill-conceived, knee-jerk, emotional responses to highly complex issues. As a whole, poor, short-sighted solutions generally result from such as there is no accountability and they are subject to whims and fads. Instead of developing unity they tend to promote a politics of divisiveness and conflict, while indirect or representative democracy is structured to facilitate compromise, moderation and the general good. Referendums can be highly destructive of the best interests of any nation. But the worst thing about referendums is that they tend to bypass the checks and balances established to protect and safeguard our freedoms—the most precious thing we have on earth. (See: “Ideals,” “Advantages” on the need for checks and balances and Mads Qvortrup and Matt Qvortrup, “A Comparative Study of Referendums: Government by the People,” Manchester University Press 2005, pp. 1-37)

Outright rebellion, an act of treason, is another terribly destructive and disheartening power. It is only justified under very rare or extreme circumstances. Simply put, it is a crime against humanity to wage war merely because one wants a change in the type of government one has. As long as a government is making a reasonable effort to protect the basic human rights of its people, it is in the best interests of everyone for that nation to stand. Nine times out of ten, it is usually the “rebels” or so-called “freedom-fighters” who destroy more rights and hurt more lives than the lawful governments they fight against.

Jean J. Burlamaqui (1694–1748), one of the founders of international law, declared that, “Indeed it would be subverting all government, to make it depend on the caprice or inconstancy of the people.” (www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2206.htm) Nothing solid, healthy and good can be built on a ruthless and lawless, or fickle society. Hence, sovereignty, that which maintains law and order and brings security to the nation, is inalienable and permanent in law. Why? Because you cannot build strong and thriving nations upon something so flimsy, weak and unstable as popularity contests, political whims or greed. There is no stability in this. Government must be based upon a sturdy foundation and that foundation is the most powerful recognized right on earth.

Sovereignty as Protective

The supreme, utlimate power of sovereignty is necessary to unify and preserve freedom, punish crimes, defend the nation and promote the general welfare. Unfortunately sovereignty, lately, has been the brunt of a lot of unwarranted and uncalled for contempt in the literature, especially in Europe, even though it is basic, and fundamental, to the unity and security of all people. For example, on an international level, without adequate respect for sovereign equality and non-intervention into the affairs of other nations, the world, as a whole, would soon lose the cooperation of nations and make the world unsafe. World powers could ruthlessly and unjustly violate a country’s territory on any pretext or whim made to sound good, and threaten their very survival. The supreme law of sovereignty in international law should protect and safeguard each individual country.

But this can only be accomplished if this core concept is respected and upheld as fundamental and indispensable. Thus sovereignty becomes a life and death issue–not a principle to be discarded as archaic and obsolete. It is not a dinosaur. Sovereignty has always existed in different terms as long as rulers have ruled. “Abandoning the concept will not erase the reality but only occlude [or obscure] it.” (Alain de Benoist, “What is Sovereignty,” p. 111: www.alaindebenoist

.com/pdf/what_is_sovereignty.pdf footnoted from Paul Hirst, “Carl Schmitt’s Decisionism,” in Chantal Mouffe, ed., The Challenge of Carl Scmitt (London: Verso, 1999), pp. 7-17) If sovereignty is a myth, as some intellectuals say, then so is the rule of law and all that holds society together. Sovereignty is the foundation of law and order, and law and order is the foundation needed for a civil, kind and gentle society to take root, thrive and prosper. Sovereignty is, therefore, essential, even critical or all important, to our peace and well-being.

Sovereign governments are, after all, the most powerful players in the world system. Diminish them and you cripple the power of the very people who can change things and make things better for all people. Hence, there is in existence “an enormously elaborate body of national and international law that secures the exclusive territory and sovereignty of the national state within and outside its jurisdiction.” (www.geocities.com/siyanurlealtin

/yazi/2002/coban/coban.html) No wonder sovereignty was defined in an international court as “a fundamental principle of international law.” It is the foundation upon which we stand. Sovereignty touches on virtually all of international law. And despite years of challenges, “sovereignty has remained resilient and robust. . . .” (http://sparky.harvard.edu/m-rcbg/bookshelf_print.htm) It has to! It holds civilization together. Thankfully, according to editors: John D. Montgomery and Nathan Glazer, it still reigns supreme “as the [chief] guiding framework for the governance of human affairs.” (Sovereignty under Challenge, 2002) So great is this principle as a bulwark of protection for civilization, prosperity and peace worldwide, that Daniel Philpott, a professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in defending it from criticism declared that “. . . the sovereign state has proven a remarkably robust form of authority, enjoying over 350 years of staying power and expanding outward to become the only form of polity in history ever to cover the land surface of the globe.” (http://libproxy.dixie.edu

:2076/journals/world_politics/v053/53.2philpott.html) For those who have eyes to see, it is any wonder that the UN Charter revolves around sovereignty as the center or the core principle of its organization. Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the UN Charter states: “The Organization is based on the sovereign equality of all its members.” (http://nationsencyclopedia

.com/United-Nations/Purposes-and-Principles-PRINCIPLES.html) “Sovereign equality” means that all states are equally supreme in their right to govern themselves without interference.

The ideology behind universal jurisdiction rests on the notion that there should be sanction for crimes which “shock the moral conscience of mankind” and that there are certain moral truths which are “right and true for every person in every society.” (United Nations War Crimes Commission, London 1948; see also International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, Judgment Against Dusko Tadic, 7 May 1997. See also Geoffrey Robertson, Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice (London: Penguin Books, 2000) and (The National Security Strategy of the United States, September 2002) However, Wolfgang Friedmann reminds us that:

In the present greatly diversified family of nations–which comprises states of starkly differing stages of economic development, as well as of conflicting political and social ideologies — the notions, for example, of “equity,” “reasonableness” or “abuse of rights” . . . do, and are bound to, differ widely. What to the one party is an abuse is to the other the reassertion of a long withheld “natural” right. (“The Uses of ‘General Principles’ in the Development of International Law” (1963) 57 A.J.I.L. 279 at 289-90)

The emotional appeal of human rights doesn’t universally fit all over the world. Therefore, the supremacy of human rights ends up being “. . . legal nonsense, in the literal sense that they have no legal meaning without being applied to specific cases or classes of cases within a legal procedure.” (John Laughland, “The crooked timber of reality: sovereignty, jurisdiction, and the confusions of human rights,” The Monist, January 1, 2007) Sovereignty like the “rule of law” has prevailed and been re-affirmed and validated as the best option to benefit all nations. This is because without the rule of law, we have nothing left but vigilantism, increased corruption and rampant insecurity. It means taking the law into one’s own hands without “due process” or any legitimate right. Obviously there is great danger in this. It would allow impulsiveness and whim to rule in international discourse. No wonder, “. . . in its international-judicial sense, [sovereignty] retains its moral, political, and legal significance. . . .” (Georg Nolte, Brad R. Roth, Helen Stacy and Gregory H. Fox, “Sovereignty: Essential, Variegated, or Irrelevant?,” American Society of International Law, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting, January 1, 2005) The results is “. . . the United Nations’ supreme judicial body . . . continue[s] to base is rulings on sovereignist jurisprudence, i.e., on recognition of the legal fact that the world is divided up into different jurisdictions, each with its own [rightful sovereign] rights and duties.” (John Laughland, 2007, op. cit.)

“The pillars of international law” are congruent and essentially the same as what is known as the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence,” that is, the seminal ideas that holds nations together. They are: (1) mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, (2) mutual non-aggression, (3) non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, (4) equality and mutual benefit and (5) peaceful co-existence. These are the most basic ideas of international law in a nutshell. Sovereignty is the foundation stone of success among nations. No wonder this principle is considered critically important. It is at the root of peace and well-being in this world. (Georg Schwarzenberger, The Fundamental Principles of International Law, note 282, p. 207 and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Principles_of_Peaceful_Coexistence) As W. Michael Reisman declared, “Our international legal system is scarcely imaginable without [territorial communities having the right to govern themselves] without interference . . . .” (“Why Regime Change Is (Almost Always) a Bad Idea,” 98 American Journal of International Law, 516, 516-17 (2004) In fact, “. . . The very existence of international law would not be possible [without sovereignty].” (Kwiecie Roman, State Sovereignty. The Reconstruction and Meaning of the Notion in International Law, 2005, p. 205)(See: “Soverignty in the Holy Roman and Byzantine Empires” & “Sovereignty: Questions and Answers”)

International Law

A major problem still lives on, however, not with sovereignty, but with the myriad of international laws currently in existence, because they sometimes violate the basic principles. And these laws are “a work in process.” They are often too fluid, too contradictory and changing, too whimsical, too political and philosophical. Putnam B. Potter, a prominent political scientist, said it well when he wrote that “international law can mean anything, like beauty which is in the ‘eyes of the beholder.” (www.womensgroup

.org/INTERLAW.html) He concluded that since “international law is largely based on custom,” and customs can be broken or have no real force behind them, therefore, international law is always in a state of flux. (Ibid.) Part of the reason for this is that international law is shaped and fashioned, even twisted and contorted to a large degree by political game playing. Therefore, it can get really complicated and it changes to suit what the major players want. In practice, because international law and politics are inseparably connected, it cannot help but be fraught with contradictions and complexities. Even their legitimacy is questionable. Some international laws are made by private companies, such as, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization—organizations without any sovereignty or elected representatives. Which, in effect, is “taxation [binding, expensive rules] without representation.” This principle was one of the primary complaints of the American colonies that brought about the war of independence from Great Britain. Needless to say international law is an imperfect system and some scholars say, it “is therefore incapable of providing a useful approach to structuring international society.” (www.ejil.org/journal/Vol4/No1/art1.html) Unfortunately, this means we must “rely on essentially contested–political–principles” to solve problems. (Ibid.) And both politics and politicians are fickle, unstable and ever changing. There is nothing comforting and solid about this.

The point here is, countries generally do what they want to, in spite of international law. For example, a legal opinion written by Willliam P. Barr, assistant Attorney General on June 21, 1989, declared that the United States “has the power to override customary international law” in certain areas. This understanding that the United States has unquestionable authority “to exercise the sovereign’s right to override international law (including obligations created by treaty) has been repeatedly recognized by courts.” (www.fas.org/irp/agency/doj/fbi/olc_override.pdf) This sovereign right is also the right of every country on earth. Even treaties can be set aside. They are not sacrosanct, but are kept only insofar as they fulfill national interests in most cases. Errol E. Harris, a well-published scholar in law and philosophy, made it clear that sovereign nations are not bound by treaties. He wrote:

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson both maintained that a nation could renounce a treaty at any time it thought fit. . . . The pages of history are littered with accounts of broken treaties. . . . The Charter of the United Nations is itself no more than a treaty. . . . Consequently, the resolutions of the Security Council have been ignored time and again, by South Africa, Israel, North Korea, and [former] Iraq — to mention only [a few]. . . .” (www.crvp.org/book/Series01/I-19/chapter

_xx.htm)

In other words, “. . . states being sovereign are at liberty to interpret a treaty in whatever way that best suits them, as they are also free to retract their commitments whenever they deem the circumstances warrant it.” (Ibid.) Pointedly, “The pages of history are littered with accounts of broken treaties.” (Ibid.) It is the rule of the day and the more common rule of the ages. “Consequently, the authority of International Law is fictional, even in theory. . . .” “Decisions agreed to in the General Assembly [ of the United Nations] are never binding; neither these nor any resolutions of the Security Council can be imposed on individual members, [because being sovereign states, ‘they are subject to no higher authority’ than their own, therefore] should they defy or ignore them . . . , [they] cannot be forced to comply except by some form of military threat.” (Ibid.) But the whole idea that treaty power is unlimited and so omnipotent and powerful that it may be used to OVERRIDE the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, the supreme law of the land, is a dangerous and foolish notion. It is also of recent origin and does not reflect traditional law and philosophy. Treaties are important, but common sense and sovereignty are not to be thrown out the window to honor some foolish or harebrained treaty that no longer applies to current events. For according to Emerich de Vattel, “Every . . . absurdity ought to be rejected [in a treaty]: or, in other words, we should not give to any piece a meaning from which any absurd consequences would follow, but must interpret it in such a manner as to avoid absurdity.” (The Law of Nations, Book II, Chapter XVII, #282) The conclusion on treaties is, “A sovereign state can make a treaty. It can also break a treaty, or determine for itself when a treaty commitment is no longer binding or applicable.” (Jeremy Rabkin, “Recalling the Case for Sovereignty” Chicago Journal of International Law, January 1 2005, p. 23) This is just good common sense and practical as well as being protective, healthy and good for all people.

The real problem, however, is that we live in a world where sovereignty, the greatest and most crucial and important international law of all, has routinely and predictably been violated by the great and the powerful of the earth. In other words, it is the views of the popular and/or the dominant that always prevails in spite of international law, treaties or the opinions and ideals of legal scholars. It all boils down to,”might makes right” or “the stronger you are, the more rights you’ll have.” If you don’t have great power or clout, if you don’t have any leverage, if you are weak and defenseless, the bullies of the world may very well oppress you and take advantage of you.

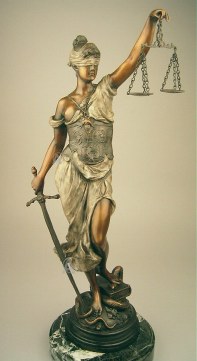

However, “the ultimate foundation [or basis] of international law is justice. . . .” (www.womensgroup.org

/INTERLAW.html) It is the universal desire of all people. We want justice. It is one of the greatest and most beautiful things there is in life. Justice legitimizes law when that law supports and upholds one of the most important principles ever conceived. And true justice recognizes inherent, inalienable rights, chiefly because those rights are just, therefore, they universally appeal to the higher nature of man.

Sir William Blackstone, the renown English jurist, declared that justice and fairness as a

. . . law of nature, being co-equal with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original. (“Of The Nature of Laws in General” 2009: http://libertariannation.org/a/f21l3.html)

He declare that any law that was “manifestly absurd or unfair” is not a “law.” He wrote, “. . . no human legislature has power to abridge or destroy . . . “those rights . . . which God and nature have established, and are therefore called natural rights, such as are life and liberty”

Emerich de Vattel, one of the fathers of international law or the law between nations, wrote his book The Law of Nations “to establish on a solid foundation the obligations and rights of nations [to promote what is just and right].” (Preliminaries to Book, note 3) This article focuses predominately on the inalienable rights of kings and sovereign princes in full accord with what is considered just and true by natural immutable law. The ancient inalienable rights of monarchy have, unfortunately, been trampled on, discarded or over looked because of our modern emphasis on different things. Nevertheless, these rights are real and they are important. In the case of Kuwait, the royal dynasty and its monarchy was fully restored after the first Gulf War, as was appropriate, and in full accord with international principles of justice.

Phillip Marshall Brown, a distinguished international lawyer, wrote on the sovereignty of kings and princes in exile, living in England, who had been robbed of the right to rule their own territories during World War II, he stated that:

A nation is much more than an outward form of territory and government. . . . So long as they [those who hold sovereignty] cherish sovereignty in their hearts their nation [kingdom or principality] is not dead. It may be prostate and helpless. . . . [It] may be suspended, in exile, a mere figment even of reality, derided and discouraged, and yet entitled to every respect. [Why? Because we are] not dealing with fictions, [these] valiant standard bearers of sovereignty . . . in faith and confidence [have, and this is the point] . . . inalienable, immutable rights. (“Sovereignty in Exile,” 35 American Journal of International Law (1941) 666-668) (http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9300(194110)35%3A4%3C666%3ASIE

%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K)

Phillip Brown went on to say, “The general conclusion we are warranted in reaching is that . . . their sovereignty, even though flaunted, restricted, and sent into exile, still persists. . . . There is no automatic extinction of nations.” (Ibid.)

However, they can be lost, which will be addressed later on. The following historical event illustrates the inherent and incorruptible rights just mentioned. The point: His Highness Emir Jaber al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah had the sovereign right to rule his own country of Kuiat and he was recognized and restored. Many other monarchies were re-established after their unlawful occupation and loss of sovereignty in World War II: Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Norway to name a few. Unfortunately, the fact is, most are never restored even though their causes are just and their claims are pure, perfect and unblemished. Justice does not always prevail in this world. Nevertheless, the claims of these lost thrones are still valid and authentic, they are legitimate and legally recognizable and acknowledged in law, whether they are honored by modern governments or not.

Royal Rights and Sovereignty

The following material, in the rest of the subchapters, will show over and over again that “de jure” sovereignty is perpetual and unending, but can be lost, with prejudice, if it is not appropriately maintained, continued and perpetuated. The ins and outs of the law will be examined. For “the nature of kingship [or monarchy], and the precise extent of royal power, were questions . . . left largely to lawyers,” that is, to the law as it was set forth and practiced from time immemorial. (Hugh N. Maclean, “Fulke Greville: Kingship and Sovereignty,” The Hunington Library Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 3, May 1953, p. 237) The law is the bedrock, core issue for the future prosperity of lawful monarchy, nobility, royalty and chivalry.

Rights

Though international law is imperfect and fails over and over again to protect the innocent and the robbed, at least it is an attempt to enthrone justice among the nations as the crowning and towering principle above all others. The basic privilege and right of sovereignty or supreme power has been around for a long time. For example, with the discovery of Roman law in the 12th century came the maxim Rex in regno suo imperator est, that is, a king is emperor in his own kingdom. (Kenneth Pennington, The Prince and the Law, 1200-1600: Sovereignty and Rights in Western Civilization, p. 3) Nevertheless, many scholars look at the Treaty of Westphalia (ratified in 1648) as the beginning of something truly great among the nations, because the rights were made a part of a treaty or, in effect, actually written into law. Professor Daniel Philpott declared:

Since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, states, now over 190 of them, have enjoyed supreme authority within their territories and immunity from external interference in enforcing their law, in organizing their national defense, in raising revenues, and in governing education, religion, their natural environments, their citizens’ economic welfare, and tens of other matters. (http://libproxy.dixie.edu:2076/journals

/world_politics/v053/53.2philpott.html)

This was the real start of international law or the attempt to recognize what is inherently right. This treaty gave decisive acknowledgement, confirmation and legal importance to the “ancient rights” of Emperors, Kings, Princes and States. It gave the idea of “ancient rights” a whole new legal power that it never had before although rights were usually, at least morally or ethically, recognized as just. But so powerful was this recognition of rights that, for example, in a dispute of the Hapsburgs of Austria in 1711, more than sixty years later, they felt compelled on the basis of this way of thinking to recognize the inviolability of the ancient rights of the Magyars, who they were quarreling with.

A “right” is defined as something to which one has a just claim, something to which one is justly entitled–like the interest that one has in a piece of property under law or custom, that is, something that one may properly claim. In fact, so important are these ancient proprietary rights that:

Commenting on the likelihood of Juan Carlos’ elevation [as king of Spain] . . . , Monarchist Mariano Robles, a lawyer and opponent of the Franco regime, declared: “It is suicide for the monarchy. It is the beginning of the end. A dictator cannot name a King. A King must succeed according to dynastic law. Otherwise it is not a monarchy, it is just a political game.” (www.time.com/time/magazine/article

/0,9171,901121,00.html?promoid=googlep)

Because HRH Don Juan de Borbon y Battenberg, Count of Barcelona, was the recognized and rightful King of Spain at that time, though he never reigned, he passed all his dynastic rights in a ceremony to King Juan Carlos I in 1977 to fully and completely legitimize and validate his son’s rule as the legitimate, rightful and lawful King of Spain. (www.sispain.org/english

/politics/royal/king.html)

These inherent rights are considered to be inalienable, immutable, incorruptible and inviolable. This means “. . . that they may not be alienated from the person who possesses them, i.e., they may not be given or taken away [without his or her consent], i.e., they may not be morally infringed upon [by any outside force]. (http://www.capitalism.org/faq

/rights.htm) But a right to something does not mean that it will be enjoyed. “For example, a man may violate your right to your property by taking it away from you, but your right to that property has not been alienated [you still hold the right], i.e., you are in the right and the robber is in the wrong.” (Ibid.) But you may never get your property back. Rights are not guarantees of success or attainment even though you are entitled to them. Emilio Furno, a supreme court attorney of Italy, explained that:

The [royal] prerogatives which we are examining may be denied [by a subsequent reigning government] . . . within the limits of its own sphere of influence [that is, within its boundaries, it] may prevent the exercise by a deposed Sovereign of his [royal] rights in the same way [just] as it may paralyze the use of any right not provided in its own legislation. However such negating action does not go to the existence of such a [legitimate “de jure”] right and bears only on its exercise. (“The Legitimacy of Non-National Orders,” Rivista Penale, No.1, January 1961, pp. 46-70)

Jean J. Burlamaqui, one of the early founding fathers and writers on international law wrote in 1748 that “The princes of the blood royal . . . certainly [have] an absolute and irrevocable [sovereign] right, of which they cannot be stripped without their consent.” (www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2204.htm) In other words, these rights are permanent and final. They can be taken away by dispossessing the monarch on a “defacto” basis by force, duress or coercion, but not on a “de jure” basis. In other words a rightful king and/or his successors who have been robbed and cheated out of their right to rule still, and will continue to, hold all the royal prerogatives of their ancient “de jure” territories as long as the family continues to live and carry on their traditions.

Sovereignty and Ownership

For the “Electors, Princes and States” of the Holy Roman Empire, these “ancient rights” were explained in the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. They were “established and confirmed” in their royal rights and prerogatives including the free exercise of their high lordships or ruling privileges “without contradiction” to create and interpret laws, declare wars, impose taxes, erect fortifications, raise armies and conclude treaties as sovereign states without interference or “molestation” of any kind whatsoever as long as it did not go against the “Public Peace” of the Empire. (www.globalpolicy.org/nations/nature/westphalia.htm) “Although technically still a part of the empire (which would last in name until 1806), these [German] principalities gained all the trappings of sovereign statehood.” (Hendrik Spruyt, “The Sovereign State and Its Competitors,” Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 29) “The Treaty of Westphalia gave virtually all the small states in the heart of Europe sovereignty, thus formally rendering the Holy Roman Emperor politically impotent [similar to a committee chairman of some 300 independent little sovereign nations loosely connected together]. . . .” (Thorbjorn L. Knutsen, “A History of International Relations Theory,” Manchester University Press, 1992, p. 71) The princes actually owned their realms which was the basis of their right to rule or govern.

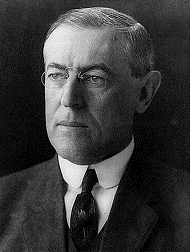

The regal rights of sovereignty in law, whether dormant or active, are a lot like ownership or property rights that are hereditary in nature. For example, The Avalon Project of Yale University concluded that the view of sovereignty taken by the earliest international jurists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was “dominium, dominion, ownership.” (www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon

/econ/int03.htm) Dominium means property. Dominion is ruling or royal authority over a territory or a people and ownership means a person is an owner of that authority and property. Woodrow Wilson, in The State, remarks, “The most notable feature of feudalism is that . . . ownership means sovereignty; he who owns the land shall have primary dominion over the fruitage of the land; he shall therefore hold in absolute subjection the dwellers on the land.” (www.materialreligion.org

/documents/nov98doc.html) That is, the sovereign, theoretically in the feudal view, is the only true owner of all the land and is, therefore, its rightful ruler.

Morris Cohen, a renowned jurist of the early 20th Century United States, explained in his famous legal essay entitled “Property and Sovereignty,” that these two are near equivalent terms. He shows that private property rights even today in law resembles the public law of “imperium”—“ the rule over all individuals by the prince” or the principle of sovereignty more than it does the concept of private property under the old Roman law of “dominium.” (1927, 156) In the Middle ages, the union between sovereignty and property was clear, that is, “The essence of feudal law . . . is the inseparable connection between land tenure and . . . genuine sovereignty. . . .” (Ibid.) But even now, property rights reflect sovereign privileges. British economist Ralph George Hawtrey in his book Economic Aspects of Sovereignty, declares that sovereignty “carries with it important economic rights which are closely related to the rights of property.” (Hawtrey, 1930, p. 18) In other words, “. . . ownership of a nation is bound up with its sovereignty. . . .” (Christian von Wolff quoted in Aboriginal Sovereignty by Henry Reynolds, p. 47) Even the word “real” in “real estate” means in French “royale” and the Spanish cognate for “real” is “royal.” In other words, “real estate” or “royal estate” was the estate of the sovereign. “Today, just like hundreds of years in the past, we pay property taxes, or rent to be on the government’s land or the Royal Estate.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_estate)

This is called the “regalian doctrince” or “jur regalia.” It:

. . . refers to ancient feudal or royal rights — the rights which the king, ruling prince or sovereign lord had by virtue of his proprietary ownership over all property in the realm. . . . [The connection between the two — ownership and soverignty has] been inseparable for thousands of years or since the dawn of civilization itself. (www.maden.hacettepe.edu.tr/dmmrt/dmmrt253.html)

This fundamental concept is still active and alive today. For example, the UN “Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States” in Article 2(1) affirms that “[e]very state has and shall freely exercise full permanent sovereignty, including possession, use and disposal, over all its wealth, natural resources and economic activities.” (www.eytv4scf.net/a29r3281.htm) UN experts have encouraged the use of “ownership” and “property of” for the word “sovereignty.” The king or sovereign lord in ancient times likewise had proprietary rights—the right to control and manage his own possession. And even though these rights are intangible or abstract, they are nevertheless, real and recognized. They are so powerful that Jean J. Burlamaqui wrote “that those kings possess the crown in full property. . . .” (www.constitution.org/burla/burla

_2107.htm) It was their personal possession–something that they owned as a royal birthright or privilege. It is similar to the concept of “allodial title” to land, that is, “held in absolute independence, without being subject to . . . or [any] acknowledgement to a superior.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allodial_title) The king or prince owned the highest right on earth to the right of sovereignty in spite of modern conventions that have unlawfully dispossessed and robbed these lawful former rulers, or their successors, of the free exercise of those rights. This basic legalistic view of things–this comparison, based upon the principle of imperium or rule and property rights, is still viable today and the full and complete ownership of these rights extends to the sovereign and his successors to perpetuity as long as they continued to exist and maintain their rightful claim. It needs to be noted here that claims can be deem to have been abandoned and such are permantantly lost and cannot be retrieved. The important principles of forfeiture and the maintenance of sovereign rights will be discussed in subsequent subchapters.

The Legal & Moral Right to be Restored

Sovereignty is Permanent and Forever, but

It can be Lost on both a “Defacto” and “De jure” Basis

First and foremost, sovereignty in a person is something very special and unique. A king, a prince, a duke, a count, etc., who held full sovereignty at one time was indeed the personification of, or the embodiment of, all the powers and glory of his nation’s regal and sovereign privileges and rights. The King was the State, and the State was the King, in ancient times. That is, the King and the State were indistinguishable or synonymous. William Blackstone explained that “the law ascribes to the king the attribute of sovereignty, or pre-eminence [in all things].” (www.financialsense.com/fsu/editorials

/gnazzo/2005/part1.html) The sovereign was the representative of all the collective power and privileges of the whole people. The king held all sovereignty. All property was owned by the monarch. It was his exclusive possession. It represented something sacred and perpetual as embodied or incarnate in the person of the King and his heirs after him. “All the majesty of the nation resides in the person of the prince. . . .” (The Law of Nations, Book I, Chapter XV, #188) And like a “de jure” right to property, it cannot be taken away. It is the notion of “absolute, unlimited power held permanently in a single person or source, inalienable, indivisible, and original” or a hereditary right to the “supreme authority within a territory.” (http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0749-6427(199921)14%3A1%3C7%3ANAIAAT

%3E2.0.CO%3B2-U) (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sovereignty)

Sovereignty, because it is supreme, above and beyond anything else, is invested with the most powerful and enduring qualities that the mind can conceive. No wonder two of the founding fathers of international law declared unequivocally that sovereignty is “permanent and irrevocable.” Other words used to describe this state of supremacy are “inseparable,” “inviolate,” “indivisible,” “perpetual,” and never ending. Jacques Maritain of Princeton University wrote that the law of sovereignty gave “. . . the king . . . supreme power which was natural and inalienable, inalienable to such a degree that [even] dethroned kings and their descendants kept this right forever [or endlessly]. . . .” (“The Concept of Sovereignty,” The American Political Science Review, vol. 44, no. 2, 1950, p. 348)

Hence, the investiture of sovereignty in a person, and his or her heirs, is considered to be sacrosanct and to be perpetual, that is, to remain intact from generation to generation forever. As long as the sovereign descendant of the former ruling house does not sell or otherwise legally surrender his or her sovereign or territorial rights to reign, it never dies and is without end. It cannot expire as long as the royal family continues and has a lawful head. In other words, with this stipulation in mind, the principle of “jure sanguines,” by right of blood, is transferred and conferred to infinity. It is a kind of secular sacrament establishing a superior claim that is passed on to ones senior surviving posterity forever. It is called “Rex Non Moritur” in British Public Law.

“The glory of a legitimate monarch is enhanced [and promoted] by the glory of those around him.” (Benjamin Constant. Political Writings, 1988, p. 91) The nobility serve as a kind of fundamental framework for the monarchy. Noble honorific titles are honors based on the sovereignty of one’s King and they reflect his splendor. But a sovereign noble prince or duke over a territory or tiny country are different. They are not normally considered royal, yet they often held the right in full, and like any true monarch, his or her sovereignty had its origin in the same four basic regal prerogatives:

(1) the “ius imperii;”

(2) the “ius gladii;”

(3) the “ius majestatis” and

(4) the “ius honorum.”

They are explained as follows:

(1) Jus Imperii is the right to command and legislate. “Jus imperii [is therefore one and the same as] the right of sovereignty.” (Professor Ruben Balane’s lectures on succession entitled, “Notes and Cases on SUCCESSION,” p. 106: www.scribd.com/doc/3004705/

UPSuccession)

(2) In addition, Jus Gladii, the right to enforce ones commands is also indespensible without which sovereignty cannot exist.

(3) Jus Majestatis, the right to be honored, respected and protected is also inseparably part of sovereignty. “. . . The `right of majesty’ (Jus Majestatis) i.e. [is an integral component of true] sovereignty. . . .” (www.scribd.com/doc/3323809

/The-First-Federalist-Johannes-Althusius-Alain-de-Benoist)

(4) Jus Honorum is the right to honor and reward. Guy Stair Sainty wrote, “. . . the jus honorum can not exist without the attribute of sovereignty. . . .” (www.chivalricorders.org

/royalty/fantasy/vigo.htm) He explained that:

This right, which is not limited only to the power to grant titles of nobility but also the faculty to bestow other marks of honor, such as pensions, knightly orders, civil and military awards, is strictly connected to the attributes of sovereignty. (Ibid.)

Continuing Mr. Sainty declared:

. . . jus honorarium, which comes from the possession of sovereignty as the other powers that characterize the sovereignty itself (such as jus imperii, jus gladii and jus majestatis) survives . . . when the effective exercise of jus imperii and jus gladii is suspended [not destroyed, but becomes dormant] by the loss, for example, of the effective control over a country. (Ibid.)

All the four prerogatives are inherent and incarnate in the person of the sovereign and his or her heirs throughout their generations forever–all the way to the end of time; chiefly, because the State and the person of the sovereign, were indivisible, giving them, the reigning or “de jure” sovereign, the full and unmitigated rights of a sovereign state. This personification or embodiment of all power was reiterated in the Law of Nations. Emerich de Vattel declared that, “The sovereign thus clothed with the public authority, with every thing that constitutes the moral personality of the nation, of course [is] . . . invested with its [the nation’s highest and most supreme] right.” (Book I, Chapter IV, #41) A king or ruling prince may not, however, be able to use the first two rightful privileges in the present constitutional framework or if they are no longer in control of their former territories. Nevertheless, all these special rights or privileges are fixed and invariable except under certain unique circumstances which will be elaborated.

The reason for this great authority and power is that “sovereignty,” derived from the French term “souverain,” means, by definition, a supreme ruler not accountable to anyone. The traditional and ongoing concept of sovereignty is that every nation, king or prince is supreme within its or his own rightful borders and acknowledges no master outside them. In other words, it is the distinguishing mark of the sovereign that he cannot in any way be subject to the commands of another power or force whether domestic or foreign. And this regal privilege is permanent and continuing to his or her heirs or alternate rightful heirs as the case may be. This is called the principle of inviolability. It “. . . means that the occupying power [the usurper, whether domestic or foreign] may obtain de facto sovereignty, but the ousted sovereign retains it de jure. (www.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_

apa_research_citation/0/7/3/8/3/pages73837/p73837-13.php)

Stephen P. Kerr, B.B.A., J.D., LL.M., M.A.T., a World Court Litigator and Special International Legal Counsel to the House of Habsburg-Lorraine and a Professor of Law at Antioch University Law School in Washington, D.C., made it clear that, “. . .de jure possession of sovereignty continues so long as the de jure ruler or government does not surrender his sovereignty to the usurper.” (See “Dynastic Law”) (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis Juris Gentium, Chapter 10, Nos. 9-11, 1680) This was once discussed by Thomas Hobbs in the 17th Century. He stated, “His [the sovereign’s] power cannot, without his consent, be transferred to another: he cannot forfeit it. . . .” (Hobbes, Lev XX 2-3) (http://etext.library.

adelaide.edu.au/h/hobbes/thomas/h68l

/complete.html)

Similarly, in the second principle of the International Commission on Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), it states that, “It is . . . considered ultra vires [beyond the control] of any republican State to interfere, by legislation or administrative practice, with Princely Dynastic Family or House Orders.” (www.icocregister.org/principles.htm) A subsequent government can make dynastic orders, titles or recognition illegal—they can ban whatever they want to in the present within their own territories, but the rights continue forever and can be exercised, if necessary, within the boundaries of a different jurisdiction, that is, in exile. Archbishop Hyginus E. Cardinale in his book stated:

A Sovereign in exile and his legitimate successor and Head of the Family continue to enjoy the ius collationis [the right to confer and enjoy honours] and therefore may bestow [such] honours in full legitimacy. . . . No authority [no matter what that authority is] can deprive them of the right to confer honours, since this prerogative belongs to them as lawful personal property iure sanguinis [by right of blood], and both its possession and exercise are inviolable.” (Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See — A historical, juridical and practical Compendium, Van Duren Publishers, Gerrands Cross, 1983, p. 119)

Carmelo Arnone, an Italian jurist, affirmed that:

Nobiliary jurisprudence assigns to a princeps natus [a blood prince or sovereign heir] a nobility by birth and such a quality attaches to the Head of a Sovereign House no longer reigning and to his successors forever.” (Diritto Nobiliare Italiano. Storia e ordinamento. Hoepli, Milano 1935, p. 189)

In other words, they are endless in nature and have important rights as “de jure” sovereigns. Professor Emilio Furno, an advocate in the Supreme Court of Appeal in Italy, wrote:

The Italian judiciary, in those cases submitted to its jurisdiction, has confirmed the prerogatives jure sanguinis [heirs and successors] of a dethroned Sovereign without any vitiation [abrogation, corruption or loss] of its effects . . . has explicitly recognised the right to confer titles of nobility and other honorifics relative to his [or her] dynastic heraldic patrimony. (“The Legitimacy of Non-National Orders”, Rivista Penale, No.1, January 1961, pp. 46-70)

Professor Furno further explains:

The qualities which render a deposed Sovereign a subject of international law are undeniable and in fact constitute an absolute personal right of which the subject may never divest himself and which needs no ratification or recognition on the part of any other authority whatsoever.” (Ibid.)

In other words, the absolute right of the deposed sovereign and his successors is a self-evident, well-known and undeniable. The whole point here is that these legal rights survive usurpation or any other form of legalized theft. Therefore, no usurper or subsequent government has the lawful power or authority to take away a family’s inalienable royal or sovereign prerogatives; not by vote, referendum, court degree, invasion, war, revolution or uprising. Why? Because such sovereigns are not accountable to anyone inside or outside of their own lawful jurisdiction. Their rights are inalienable unless voluntarily discarded.

For example, in a republic, it is assumed as a legal presumption that sovereignty is possessed by all individuals in a state under natural law, but the point here is, “Once the people [have] . . . given the king and his descendants power over them . . . the natural right to govern the body politic resided henceforth in full only in the person of the king.” (http://libproxy.dixie

.edu:2076/journals/world_politics/v053/53.2philpott.html) A referendum to throw out the monarchy and establish a republic (an unjustified revolt) is really nothing more than a collective act of treachery and sedition against the highest and most important power of the land. This is because sovereignty is legally the “ultimate authority held by a person or institution, against which there is no appeal.” (www.encyclopedia.com/doc

/1O142-sovereignty.html) Jean Jacques Burlamaqui (1694–1748), was one of the fathers of international law. He wrote, “Whosoever therefore rises against the sovereign, or makes an attack upon his person or authority, renders himself manifestly guilty of the greatest crime, which a man can commit. . . .” (Jean Jacques Burlamaqui: www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2206.htm) That is, it would be an act of treason and those who committed such a crime were, as individuals, traitors to king and country. This may seem radical or extreme, but kingdoms and principalities were destroyed and rightful sovereignty stolen many times by this kind of criminal act.

However, as Emerich de Vattel wrote: “If the body of the nation declare that the king has forfeited his right, by the abuse he has made of it, and depose him, they may justly do it when their grievances are well founded. . . .” (The Law of Nations, Book II, Chapter XII, #196) But, such an act does not eliminate the rights of the royal family and the next in line is still the rightful heir and should replace a tyranical king. However, a reigning king cannot be thrown out by mere political whim, or just because the people might want to do so, because it is popular or the newest fad. This simply cannot be done unless such an action is agreed to by the king himself, because it is a crime of the greatest treachery to fight or depose him. It is an act of treason.

Jean Jacques Burlamaqui brought up the common sense or self-evident notion that no man is perfect, which includes the prince of the land. He said, “We must indeed make some allowance for the weakness inseparable from humanity.” (www.constitution.org/burla/burla 2206.htm) No king is going to be perfect, but if the king is reasonably good, it is a crime of the worst kind to oppose him and speak evil of him. “Thou shalt not . . . curse the ruler of thy people.” (Eodus 22:28)

The point is, “. . . the whole body of the nation, have not a right to depose the sovereign. . . ,” if he is basically good—popularity has nothing to do with what is right and just. (Ibid.) In other words, “. . . they [the people] that are subjects to a monarch, cannot without his leave [his permission or consent] cast off monarchy. . . . If they depose him, they take [rob, steal or plunder] from him that which is his own [his and his successor’s possession if hereditary], and so again it is injustice [a wrong or a violation].” (Thomas Hobbes, Hobbes’s Leviathan. Harrington’s Oceana. Famous Pamphlets. (A.D. 1644 to A.D 1785, 1889, chapter XVIII, p. 85)

The people just do not have this right unless the king is a genuine tyrant or truly oppressive. However, even if such a despotic king is rightfully thrown out and deprived of his throne, it must be remembered that his heirs still have the right to rule in his place and to succeed him with all his former rights and royal prerogatives. Disposing of an evil king does not give a country the right to throw out the royal and/or collateral family and set up a different form of government or create a new royal house. The “. . . will of the people [by referendum or revolt, etc.], without the [willing, not coerced or forced] consent of the prince [the rightful monarch or his successor], cannot deprive his children. . . [or take away their lawful right to rule].” (J. J. Burlamaqui: www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2204.htm) This right is permanent and perpetual.

“. . . The people [do] have a right to resist a tyrant, or even to depose him.” (www.lonang.com/exlibris/burlamaqui/burl-2206.htm) But this right does not belong to “. . . the vile populace or dregs of a country, nor the cabal of a small number of seditious persons, but the greatest [the best] and most judicious part of the subjects of all orders in the kingdom. The tyranny, as we have also observed, must be notorious [obvious, even self-evident], and accompanied with the highest evidence. (Ibid.) Otherwise it is forbidden. It is wrong to precipitate in violence and civil strife, endangering the lives of the innocent.

Obedience to a basically good and rightful ruler, or his lawful successor, is a “. . . [duty, obligation or a just responsibility] of subjects [citizens of the nation] to their sovereigns . . . [ie.] the person of the sovereign should be [held] sacred and inviolable.” (Jean Jacques Burlamaqui: www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2205.htm) In fact, “It is this obligation to obedience in the subjects [the citizens of the nation], that constitutes the whole force of civil society and government. . . .” (Ibid.) It is fundamental to everything good, just and right to preserve the prosperity and peace of the a nation.

The point is, “. . . Subjects are not allowed to use these means [violence or the coercive force of a referendum] against their King or Prince. . . .” (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 88) In other words, “The king . . . cannot be deprived of his sovereignty, acquired legitimately, unless he lapses into tryanny.” (A. Robert Lauer, Tyranicide and Drama, 1987, p. 66) “Subjects [have] . . . no legal right to deprive their ruler of his office.” (Charlotte Catherine Wells, Law and Citizenship in Early Modern France, Issue 1, 1995, p. 198) “[In fact, legally] it would be impossible to legitimately dispose of [a monarch], without a cession or renunciation on their part. . . .” (Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Memoirs of the Prince de Talleyrand, vol. 2, 1891, p. 160) That is, he cannot be impeached unless he freely and willingly agrees. The point is, sovereignty being supreme and above all authority, therefore, “. . . legally, a sovereign could not be resisted or deposed. [Why? — because] sovereignty [legally and lawfully] is absolute and indivisible [and above all].” (The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, David Miller, Janet Coleman, William Connolly & Allen Ryan, eds., 1991, p. 2)

No referendum, nor conquest, nor any other act of sedition or illegality can rob a legitimate and rightful monarch of his right to title and right to rule. Jean Burlamaqui made it clear that if the king is basically good, not perfect, but basically good (we are not discussing criminal tyrants here), “. . . the right of disposing of the kingdom returns to the nation” only under one type of situation—only if the sovereign family that has the right of succession to the crown, or their close relatives who also have dormant succession rights, no longer exist or no longer proclaim their right to the throne. (www.constitution.org/burla/burla_2203.htm) Then and only then can a nation reclaim rightful sovereignty from the royal or princely family. What has happened too often in the past is theft, pure and simple, of the “defacto” realm—the unlawful plunder of the government of a whole nation from its rightful rulers, which is an act of treason.

In terms of these sovereign rights, the highest rights on earth, royal families have the pinnacle of power, higher and greater than anyone else on earth—higher than any subsequent legislative body to rule their former territories. Their authority is absolute and supreme as pertaining to their “de jure” or lost territory, whether it be a sovereign county, principality, dukedom, kingdom or empire and this is true even though it no longer exists or the old boundaries have been changed.

However, there is an important difference between an “overthrown monarch” and one who has accepted the new political order that has taken over. Those who accept it lose everything — they lose all sovereginty [or any] right to Pretention. On the other hand, a monarch even though he has suffered dethronement has no loss of rights, because consent is lacking. A deposed sovereign can lose his regal prerogatives only as a consequence of political capitulation or acquiescence which is sometimes called “debellatio.” (Ibid.) “Debellatio” means there is no one who will assert, maintain or continue governmental rights, because the defeated state has ceased to exist. If the sovereign or monarch survives and gives up, or willingily gives in, to such treachery, that is the end of his royalty and that of his posterity, if the living successors do not protest and claim their rights.

It is as Johann Wolfgang Textor von Goethe, (1749-1832) the famous German publicist and International lawyer, quoted earlier declared:

. . . a King who has been driven from his Kingdom by force of arms, and has lost possession of his [territorial or defacto] sovereignty, has not thereby lost his right, or at any rate not irrevocably, unless he has in the meanwhile given his assent [his acquiescence] thereto; but he loses it conclusively at the moment when he consents [acquiesces] to transfer of it to the Estates, i.e. Parliament or to his rebel subjects, and then it must be recognized that the Kingdom has been made into a State which has been founded in accordance with the Law of Nations. (Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 88)